African Consumer Leaders’ Conference on Biotechnology & Food Security, November 18-20, Lusaka, Zambia

Dr. Mae-Wan Ho, Director, Institute of Science in Society

I am, and have been a scientist for nearly 40 years. Science is still my first love, and I never thought I’d be doing many of the things I am doing now, like speaking at this conference.

The reason I am here today is because back in 1994, I was invited to another conference, "Redefining the life sciences", organised by my friends Martin Khor, Vandana Shiva, Tewolde Egziabhar and others. Instead of the usual academic talk-shop I was expecting, it became clear that redefining the life sciences was a matter of life and death for family farmers, especially those practising small-scale sustainable farming dependent on natural and agricultural biodiversity. They were just getting over the devastation caused by the monoculture crops of the green revolution; but the GM crops of the gene revolution were promising far worse.

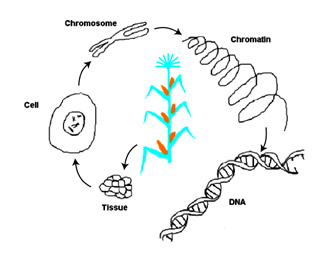

Slide 1 – From organism to DNA

I had left genetics behind five years earlier in 1989, and found a different kind of science. (By the way, not all scientists are genetic engineers, they are a tiny fraction of all scientists. Similarly, the world of science is much, much larger than just genetic engineering.) At the time, all the scientific findings already indicated that genetic engineering was unlikely to work and could be dangerous. But the quality of the information given out was so poor, and that was how I got involved in informing the public and the policy makers.

The old picture of genetics - with genes remaining almost constant in a static genome, determining the characteristics of the organism in linear chains of command - has had to be overwritten many times.

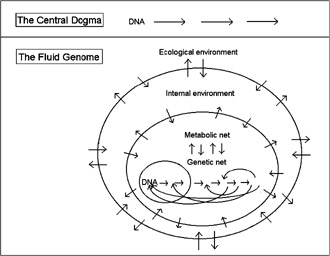

Slide 2 – Genetics old and new

Geneticists discovered huge complexities leading from the genes to perhaps a thousand times as many proteins as there are genes. Different combinations of proteins are active in individual cells at different times, depending on multiple levels of feedback from the environment. This feedback changes not just the function of genes, but the genes and genomes themselves. Furthermore, the genetic material of one species can be taken up and incorporated into the genome of totally unrelated species. Genetic engineering simply does not make sense given the complexity and especially the ‘fluidity’ of genes and genomes in both structure and function.

And sure enough, the GM enterprise (GM crops & gene medicines both) is collapsing, most of all because it is not working. There have been no benefits documented by independent scientific studies. On the contrary, there have been reduced yields, inconsistent performances in the fields, increased pesticide and herbicide use, and loss in earnings for farmers.

The predicted ‘biotech boom’ never happened. Biotech market shares peaked in 2000, but have been falling sharply since, and staying well below the industrial average on both sides of the Atlantic. Thousands have lost their jobs in mass layoffs even from the genomics and pharmaceutical sector.

The UK Soil Association’s study released in September found GM crops an economic disaster. They have cost the United States an estimated $12billion in farm subsidies, lost sales and product recalls due to transgenic contamination. The farmers came to Britain to tell of their ordeal, and to say to us: do not allow our nightmares to become yours.

Slide 3 – GM failure in Munlochy, Scotland, photographed by Munlochy vigil.

Catastrophic failures of GM cotton, up to 100%, have been reported in several Indian states, including non-germination of seeds, root-rot and attacks by the American bollworm, for which the crops are supposed to be resistant. A university-based study has confirmed that the Bt-cotton was up to 80% infested with the bollworm.

These failures have been occurring all over the world. Here’s an example documented by a local protest group in Scotland.

Monsanto has been teetering on the brink of oblivion since the beginning of 2002 as one company after another spun off their agricultural biotechnology. It has suffered a series of setbacks: drastic reductions in profits, problems in selling GM seeds in the US and Argentina.

Biotech giant Syngenta is deserting Britain’s top plant biotech research institute, John Innes Centre, even as the latter’s publicly funded Genomics Centre is being unveiled.

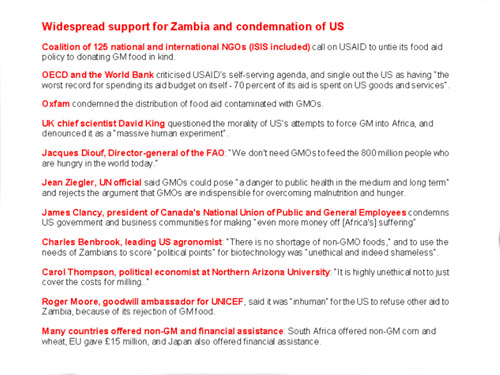

Instead of letting the industry sink, the US government, with the help of the World Food Programme is buying up the GM produce that they cannot sell, and dumping it on famine-stricken nations. It is an act of sheer desperation and wickedness that has been widely condemned; especially when it became clear that there is plenty of non-GM maize available in the US. Zambia received widespread support.

Slide 4 - Support for Zambia.

Our governments have already squandered billions in tax subsidies and other give-aways to the industry over the years. They are now wasting further billions to prop up a sinking titanic of enterprise that’s morally, scientifically as well as financially bankrupt.

At the same time, the corporations are aggressively taking over our national and international institutions. An emerging ‘academic-industrial-military complex’ is threatening to engineer both life and mind.

Corporations have taken control of public funding agencies, to determine which kinds of scientific research can get done. With the help of the government and the scientific establishment, they also determine which scientific findings can get reported. Scientists who report adverse findings can get sacked.

Syngenta is now on the governing board of CGIAR, which oversees many international research centres. This new management will greatly facilitate organised biopiracy of CGIAR’s GeneBanks, which contain ex situ collections of indigenous plant varieties from around the world.

Evidence of the hazards inherent to GM technology is being confirmed. Among the most serious, if not the most serious hazard is horizontal gene transfer. I have alerted our regulators at least since 1996, when there was already sufficient evidence to suggest that transgenic DNA in GM crops and products can spread by being taken up directly by viruses and bacteria as well as plant and animals cells.

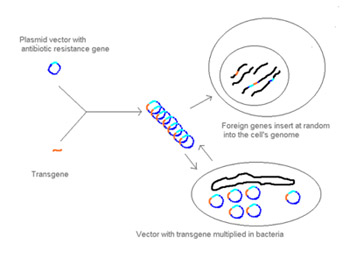

Slide 5 - How to make a GMO.

In order to appreciate the dangers, you have to know how GMOs are made.

The oft-repeated refrain that "transgenic DNA is just like ordinary DNA" is false. Transgenic DNA is in many respects optimised for horizontal gene transfer. It is designed to cross species barriers and to jump into genomes. It contains DNA of many species and their genetic parasites (plasmids, transposons and viruses), and can therefore more easily transfer genes to all of them. Transgenic constructs contain new combinations of genes that have never existed, and they also amplify gene products that have never been part of our food chain, raising serious concerns of toxicity and allergenicity.

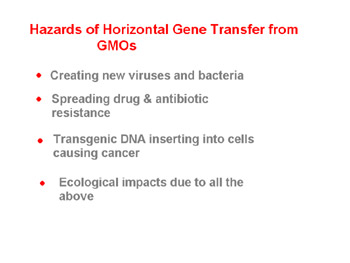

Slide 6 - Hazards of horizontal gene transfer

The health risks of horizontal gene transfer include:

The risk of cancer is highlighted by the recent report that gene therapy - genetic modification of human cells - claimed its first cancer victim. The procedure, in which bone marrow cells are genetically modified outside the body and re-implanted, was previously thought to avoid creating infectious viruses and causing cancer, both recognized major hazards of gene therapy.

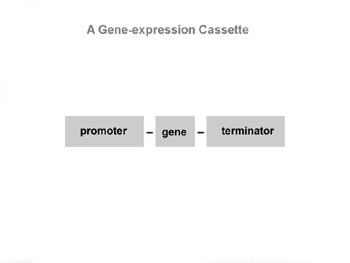

The transgenic constructs used in genetic modification are basically the same whether it is of human cells or of other animals and plants. The foreign gene or transgene, needs to be accompanied by a promoter – a gene switch. An aggressive promoter from a virus is frequently used to boost the expression of the transgene. In plants, the 35S promoter from the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) is widely used.

Slide 7 - A gene-expression cassette

Unfortunately, although the virus is specific for plants of the cabbage family, its promoter is active in species across the living world, human cells included, as we discovered in the scientific literature dating back to 1989. Plant geneticists who have incorporated the promoter into practically all GM crops now grown commercially are apparently unaware of this crucial information.

In 1999, another serious problem with the CaMV 35S promoter was identified: it has a ‘recombination hotspot’ where it tends to break and join up with other DNA. Since then, we have continued to warn our regulators that the promoter will be extra prone to spread by horizontal gene transfer and recombination. The controversy over the transgenic contamination of the Mexican landraces hinges on observations suggesting that the transgenic DNA with the CaMV 35S promoter is "fragmenting and promiscuously scattering throughout the genome" of the landraces, observations that would be consistent with our expectations.

Similarly, I was not surprised by the research results released earlier this year by the UK Food Standards Agency, indicating that transgenic DNA from GM soya flour, eaten in a single hamburger and milk shake meal, was found transferred to the bacteria in the gut contents of human volunteers.

The Agency immediately dismissed the findings and downplayed the risks in an attempt to mislead the public, and I have challenged the Agency in the strongest terms.

First, the experiment was already designed to stack the odds heavily against finding a positive result. For example, the probe for transgenic DNA covered only a tiny fraction of the entire construct. So, only a correspondingly tiny fraction of the actual transfers would ever be detected, especially given the well-known tendency of transgenic constructs to fragment and rearrange.

Second, the scope of the investigation was intentionally restricted. There was no attempt to look for transgenic DNA in the blood and blood cells, even though scientific reports dating back to the early 1990s had already provided evidence that transgenic DNA could pass through the intestine and the placenta, and become incorporated into the blood cells, liver and spleen cells and cells of the foetus and newborn.

Third, no attempt was made to address the limitations of the detection method and the scope of the investigation, which grossly underestimated the extent and frequency of horizontal gene transfer, and hence failed completely in assessing the real risks. On the contrary, false assurances were made that "humans were not at risk".

Another research project commissioned by our government concerns Agrobacterium tumefaciens, the soil bacterium causing crown gall disease. This bacterium has been developed as a major gene transfer vector to make transgenic plants. Foreign genes are typically spliced into T-DNA - part of a plasmid called Ti (tumour-inducing) – that’s integrated into plant genome.

It turns out that Agrobacterium injects T-DNA into plant cells in a process that strongly resembles conjugation, ie, mating between bacterial cells; and all the necessary signals and genes involved are interchangeable with those for conjugation.

That means transgenic plants created by T-DNA vector system have a ready route for horizontal gene escape, via Agrobacterium, helped by the ordinary conjugative mechanisms of many other bacteria that cause diseases.

The scientific report submitted to the government had indeed raised the possibility that Agrobacterium tumefaciens could be a vector for gene escape.

The researchers found that it extremely difficult to get rid of the Agrobacterium vector from the transgenic plants, which remain contaminated a year and a half later.

High rates of gene transfer are known to be associated with the plant root system and the germinating seed. So, Agrobacterium could multiply and transfer transgenic DNA to other bacteria, as well as to the next crop planted in the soil.

Agrobacterium was also found to deliver genes into several types of human cells, and in a manner similar to that which it uses to deliver genes into plant cells.

The UK Food Standards Agency had failed to reply to my repeated challenges. I tabled my questions again together with some obvious experiments they should have done at the an Open Meeting of the scientific advisory committee for novel foods on 13 November, just a few days before I came here. And I also turned up in person to demand a response.

As I expected, they have no answers, not the entire scientific committee, nor the extra expert invited to respond to me. They conceded that I have raised "some interesting points", which "can be addressed by further experiments" along the lines that I suggested.

All the risks of horizontal gene transfer I have described are real, and far outweigh any potential benefits that GM crops can offer. There is no case for allowing any commercial release of GM crops and food products, especially now.

Multi-herbicide tolerant GM canola volunteers have appeared rapidly in Canada and the United States, constituting serious weeds, as many critics have predicted.

Roundup-tolerant super-weeds are plaguing GM soya and cotton fields in the US.

Transgenic contamination of both established seed stocks and indigenous landraces is widespread, threatening both agricultural and natural biodiversity. But worse is yet to come.

On November 11, the US government ordered the biotech company, ProdiGene, to destroy 500,000 bushels of soybeans in Nebraska contaminated with transgenic maize engineered to produce pharmaceuticals not approved for human consumption. A day later, the US government disclosed that ProdiGene did the same thing in Iowa back in September, when the USDA ordered 155 acres of nearby maize to be incinerated for fear of contamination.

More than 300 field trials of similar pharm crops have been conducted in secret since 1991, to produce vaccines, growth hormones, clotting agents, industrial enzymes, human antibodies, contraceptives, abortion-inducing drugs, and immune-suppressive proteins.

The four main centres are Nebraska, Wisconsin, Hawaii and Puerto Rico, the last location being regularly used for GM seed production because there are four growing seasons a years. The true extent of such poisoning of our food supply is not known. My colleague Prof. Joe Cummins found these crops growing unannounced in Canada. Someone from Bangladesh recently contacted us to say that similar trials are planned there. We have repeatedly warned against such pharm crops since 1998.

Not surprisingly, there is worldwide rejection of GM crops. Zambia is not alone.

One hundred percent of the wheat buyers in China, Korea and Japan have announced they will not buy GM wheat. The rejection rates from Taiwan and South East Asia are 82% and 78% respectively.

China has cancelled plans to commercialise Bt cotton and dampening down on development of GM crops in general.

Farmers and retailers in Switzerland have agreed never to produce or sell GM food.

Europe’s moratorium is holding firm for two reasons. Its new Directive, which came into effect on 17 October, requires a full environmental risk assessment and other strict measures that would exclude most GMOs. Second, lifting the moratorium depends on the EU environment ministers approving legislation on the labelling and traceability of GM crops. But agreement is a long way off, with a hard core of member states, led by France, wanting a lower threshold. They also want labelling to apply to processed foods in which GM traces have been destroyed, and to animal products such as eggs and milk.

Brazil’s new president wants to keep Brazil GM-free.

The elite French three-star chefs have launched a ‘crusade’ for a Europe-wide ban on GM crops and livestocks.

Governments all over the world have legislated or are in the process of legislating tough biosafety laws to exclude GM crops and products.

In contrast to GM crops, the evidence in favour of a non-GM, organic, sustainable option is now firmly documented. There is little or no reduction in yields in developed countries, with yields improving in successive years. But it is in developing countries that low-input, organic, or agro-ecological approaches are working miracles. Three to four fold increases in yield are frequent. There are many additional benefits: improvements to soil fertility, increased sequestration of carbon in the soil, health, cleaner environment, reduction in food miles, self-sufficiency for farmers and both financial and social enrichments of local communities.

At a very early stage in the genetic engineering debate, I became aware that the debate was no less than a global struggle to reinstate holistic knowledge systems and sustainable ways of life that have been marginalized and destroyed by the dominant, unsustainable monetary culture.

Knowledge itself is under threat in many ways. Globally, the new Trade-Related Intellectual Properties (TRIPS) regime of industrialised nations, which includes patents of organisms, human genes and cell lines, is being imposed on the rest of the world through the World Trade Organisation (WTO), as part of a relentless drive towards economic globalisation. The TRIPS regime is an unprecedented privatisation of knowledge. It has also led to widespread biopiracy of indigenous knowledge and resources, threatening local biodiversity and the livelihoods of indigenous communities.

Farmers in Canada and the United States who found their fields contaminated by patented crop genes have been ordered by the courts to pay compensation to Monsanto. This is a foretaste of the corporate serfdom that bad science + big business is leading us to, if we don’t stop to it now.

Slide 8 - Another world is possible

"Another world is possible" was the rallying cry of the fifty thousand who gathered in Porto Alegre in February for the Second World Social Forum (WSF), to voice unanimous opposition to the present economic globalisation.

I was so inspired that I produced the first draft of a discussion paper, Towards a Convention of Knowledge, which has received widespread input and support from scientists, Third World and indigenous peoples’ representatives. This Convention is intended to serve as a focus of a concerted campaign to reclaim all knowledge systems for public good, to build another possible world.

I do believe another world is possible, and it is within our reach. Zambia has led the way in resisting the ultimate moral blackmail from the corporate powers. It is time for decisive action. Let’s stop this dangerous experiment now, and opt for a GM-free world, so farmers in Africa and elsewhere can get on with sustainable farming for health, self-sufficiency and genuine wealth, not in monetary terms, but in social and natural goods.

Article first published 28/11/02

Got something to say about this page? Comment