The ‘Deadly Dangers of Saturated Fat’ and the ‘Superlative Safety of Statins’ Part 2

A scandalous history of scientists for hire, revolving door between food industry and regulators, not-for-profit NGOs hungry for funding, plain bad science, and fake TV commercials; sounds familiar by now? Dr. Paul J Rosch

The ‘Deadly Dangers of Saturated Fat’ & ‘Superlative Safety of Statins’ Part I [1] reviewed some of the compelling evidence that saturated fat does not cause coronary disease by elevating serum cholesterol or any other mechanism. So how did restricting fat intake become official US government policy?

In 1961, the American Heart Association published its first dietary guidelines, in which Ancel Keys, Irving Page, Jeremiah Stamler and Frederick Stare, strongly advised substituting polyunsaturated fatty acids for saturated fat [2]. This despite the fact that in a 1956 paper, Keys proposed that the increasing use of hydrogenated vegetable oils might actually be the underlying cause of the current heart attack epidemic [3]. Page and Stare had also previously published papers showing that the increase in coronary heart disease mirrored the rise in consumption of vegetable oils. Nevertheless, Stamler, sponsored by Mazola Corn Oil and Mazola Margarine, co-authored “Your Heart Has Nine Lives” urging people to substitute vegetable oils for butter and other “artery clogging” saturated fats [4]. Mazola advertisements also claimed that “science finds corn oil important to your health,” even though there was no evidence whatsoever.

The US Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs chaired by Senator George McGovern was established in 1968 to study the problem of malnutrition. In 1974, McGovern expanded the Committee's scope to include national nutrition policy and the focus shifted from malnutrition to eating too much, especially fats. Their 1977 report, Dietary goals for the United States, was based on the belief that eliminating fat would lower cholesterol and reverse the rising incidence of heart disease [5]. It was also strongly influenced by the food industry, and was written by Nick Mottern, a former labour reporter for The Providence Journal, who had no scientific background and no experience writing about science, nutrition, or health [6]. He relied heavily on Professor of Nutrition at Harvard Medical School Mark Hegsted, who maintained that saturated fats elevated harmful cholesterol levels, and should be replaced by monosaturated and polyunsaturated fats that could have beneficial effects [7].

Mottern, a vegetarian, believed saturated fat to be as dangerous as cigarettes, and urged everyone to cut total fat intake to 30 % of total calories, limit saturated fat to 10 %, and increase carbohydrates to 55-60 %. The National Advisory Committee proposed a similar diet in the UK in 1983 even though no benefits had ever been reported from this or other fat restricted diets [8]. A very recent thorough investigation of all the randomized clinical trials that were available prior to 1983 concluded that this diet should never have been introduced [9]. Critics also pointed out that populations with the lowest rates of heart disease had high intakes of saturated fat. The Inuit Eskimos lived long healthy lives free of heart disease and cancer despite the fact that 75 % of caloric intake was saturated fat from whale meat and blubber. Saturated fat was 66 % of total calories for the Masai in Kenya, who consumed of large amounts of meat and milk. Yet, heart disease was rare and cholesterol levels were about half those of the average American. And human mother’s milk, which is 54 % saturated fat, could hardly be considered dangerous or unhealthy.

Others quickly got onto this “heart healthy” substitution bandwagon, which was becoming a juggernaut. Wesson recommended its cooking oil “for your heart’s sake” and a Journal of the American Medical Association advertisement described Wesson oil as a “cholesterol depressant”. Other medical and lay journal advertisements advised patients with high blood pressure to replace butter with Fleischman’s unsalted margarine. Dr Frederick Stare, head of Harvard’s Nutrition Department, recommended taking up to one cup of corn oil daily in his syndicated column, and wrote promotional articles for Procter and Gamble’s Puritan Oil. Dr William Castelli, Director of the Framingham Study was one of several other leading authorities that promoted Puritan Oil and Dr Antonio Gotto, Jr., a former American Heart Association president, sent a letter praising Puritan Oil to all practicing physicians printed on stationery with the letterhead Baylor College of Medicine, The De Bakey Heart Center [10]. He was apparently unaware that Dr Michael De Bakey, the preeminent heart surgeon, had co-authored a 1964 study involving 1 700 patients that showed no correlation between serum cholesterol levels and the severity or extent of coronary disease [11].

The 1977 McGovern report was not well received and objections came from leading authorities like Rockefeller University’s Edward “Pete” Ahrens, and NHLBI Director Robert Levy, both of whom argued that nobody knew if eating less fat or lowering blood cholesterol levels would prevent heart attacks. The American Medical Association warned that the proposed diet raised the "potential for harmful effects" and others described it as a "dangerous public health experiment". When Dr. Robert Olson urged "more research on the problem before making announcements to the American public", McGovern's response was "I would only argue that Senators don’t have the luxury that the research scientist does, of waiting until every last shred of evidence is in." There can be little doubt about which side McGovern favoured, as he had spent a month at a Pritikin Longevity Center, with its draconian diet of less than 10 % of total calories from fat and 2 % from saturated fat. He told a reporter that he adhered to the diet as much as possible and regarded Pritikin “one of the really great men I've known in my life."

Dairy, egg, and cattle industry representatives from farming states, including McGovern's own South Dakota, vigorously opposed the guidelines for other obvious reasons. They also complained that the report was biased and not based on any solid evidence of efficacy or safety. As a result, additional hearings were held and a revised edition that was published several months later softened the restriction on eating meat. As their work was finished, the McGovern committee was due to expire at the end of 1997, but the Department of Agriculture was anxious to promote their recommendations, because a low fat-high carbohydrate diet would increase the sale of grains. In July 1977, Carol Foreman, a powerful consumer activist was appointed Assistant Secretary of Agriculture for food and consumer services. Her goal was to make the McGovern recommendations official US policy and to increase the USDA’s influence and participation in making all future dietary decisions.

She recognized this would require backing from respected scientists and organizations and the best and most appropriate resource would have been the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), which determines the Recommended Dietary Allowances of calories and nutrients. However, NAS President, Philip Handler, an expert on metabolism, told Foreman that Mottern's report was “nonsense”. Frustrated, she consulted McGovern's staff and they suggested hiring Hegsted, who was appointed in 1978 as USDA Administrator of Human Nutrition. Although there was no scientific support for him to find, The American Society for Clinical Nutrition had recently assembled a panel of nine experts to study the relationship between dietary practices and health outcomes. They had six recommendations that included avoiding excessive sugar, salt, alcohol and total calories, as well as cholesterol and fat, but did not provide any percentages for the latter [12]. These recommendations were included in the 1979 "Healthy People: The Surgeon General's Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention", which specified that the evidence for fat and saturated fat came from animal studies, but did not list any references [13]. In 1980, the USDA and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued their joint “Dietary Guidelines for Americans” which recommended reducing saturated fat to less than 10% of total calories [14]. (This has persisted and will likely be the same for 2015.)

In an article commenting on the dietary guidelines, Hegsted acknowledged the difficulties in getting reliable information on dietary intake in humans, and extrapolating results on middle-aged men to women, children and the elderly [15]. In 1981, he returned to Harvard to do research sponsored by Frito-Lay on the benefits of substituting Olestra cooking oil for fat. Carol Foreman had also left the FDA to become president and co-founder of a powerful PR and lobbying company whose clients included Philip Morris, Monsanto (maker of genetically engineered corn and bovine growth hormone), Procter & Gamble (maker of the fake fat Olestra) and other huge food and drug companies. Frito-Lay was subsequently sued for labelling its GMO content as “natural”, and to avoid an additional lawsuit, agreed to emphasize on all labelling and advertisements that their low calorie chips contained Olestra. Olestra is banned in the Europe, Canada and Australia because it blocks the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and can cause severe abdominal cramps.

The revolving door between industry executives or lobbyists and Federal regulatory agencies is not unusual, particularly with respect to the FDA and drug companies. It helps to explain why official recommendations are often designed to increase profits rather than improve health or prevent disease. This is aided and abetted by support from respected organizations and authorities that receive lavish funding from vested interests. As Dr Marcia Angell wrote in her 2004 book The Truth about the Drug Companies: How They Deceive Us and What to Do about It [16]:

“This industry uses its wealth and power to co-opt every institution that might stand in its way, including the U.S. Congress, the Food and Drug Administration, academic medical centers and the medical profession itself. . . . It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as an editor of The New England Journal of Medicine.”

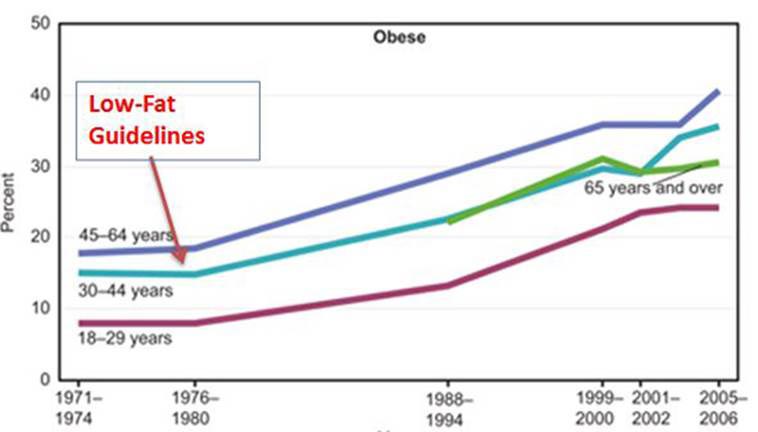

Things have gotten worse rather than better since then but drug companies are not the only offenders. Because of the low fat craze, food manufacturers eliminated or reduced fat in their products, but this detracted from their taste, so large amounts of fructose were added to make them appealing, especially for soft drinks. This was later found to have serious health consequences, including the development of metabolic syndrome (hypertension, increased abdominal fat, Type 2 diabetes, elevated triglycerides, low HDL) and increased risk of coronary disease [17-19]. It is no coincidence that the present obesity epidemic started precisely after these low fat guidelines were first published [20]. Thesteady rise in obesity in different age groups since then can be seenin Figure 1 [21].

Figure 1 Rise in obesity coincides with introduction of Dietary Guidelines for Americans [21]

The American Heart Association (AHA), a nonprofit organization whose annual income now approaches $800 million, began its Heart-Check Certification Program in 1995. This allowed companies to advertise their products as “heart healthy” by displaying the AHA red heart with a white check mark logo. The first-year fee was $7 500 per product and $4 500 for annual renewals. Certification now costing up to $700 000 has been extended to menus and restaurants, and the 700 or so certified products are in six categories that include different types of “Extra Lean” meat and seafood, certain nuts and grains, fish with required level of omega-3 fatty acids, etc. Unfortunately, among those recommended are chocolate milk, high sugar breakfast cereals, processed meats full of chemicals and preservative and other products that are anything but healthy.

Advertising is also misleading. Welch’s “Healthy Heart” 100 % Grape Juice is a proud recipient of certification but is sweetened by fructose. An 8-ounce serving contains 36 grams of sugar and 140 calories, about one-third more than the same amount of Coca-Cola. Their Concord Grape Juice Cocktail is only 25 % juice and contains high fructose corn syrup. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the “world’s largest organization of food and nutrition professionals”, (formerly the American Dietetic Association or ADA), educates and licenses registered dietitians. Its largest sponsors include over a dozen junk food companies like Coca-Cola, Pepsico and Mars that provide educational courses claiming that sugar is healthy for children. There are numerous other examples, as the words “low-fat” or “fat-free” on packaging usually mean that it is a highly processed product loaded with sugar, especially fructose.

As Mark Twain noted, “There are three types of mendacity in the world, lies, damn lies and statistics.” The 1st law of statistics is that if it does not support your theory, you need more statistics. The 2nd law is that given enough statistics you can prove anything; like expert witnesses, they can be used to testify for either side. Proponents of cholesterol lowering drugs have utilized this to great advantage, starting with the 1984 NIH Lipid Research Clinics’ Coronary Primary Prevention Trial (LRC-CPPT) [22]. It predicted that taking cholestyramine for 7-8 years would lower cholesterol by 28 % and result in a 50 % reduction in coronary morbidity and mortality. Although these goals were not obtained, the authors reported a 19 % decrease in nonfatal coronary events and 30 % fewer heart attack deaths. This was the first study to demonstrate that lowering cholesterol could prevent coronary disease and deaths, and headlines triumphantly trumpeted “The Lipid Hypothesis Is Finally Proven” and “Coronary Disease Prevention: Proof of the Anticholesterol Pudding.” It also served as the basis for establishing The National Cholesterol Education Program the following year, which is still in effect.

But the 19 % and 30 % were relative risk factors obtained by comparing the number of individuals affected in each group. The actual risk factors were only an insignificant 1.1 % for nonfatal cardiac events and 2.3 % for fatal heart attacks. For example, if only 1 person in a treatment group died compared to 2 in the control group, the relative risk reduction would be 50% (1 divided by 2.) But if there were 1 000 people in each group, the actual risk reduction is 0.1 % (0.2% minus 0.1%). It is also important to emphasize that it took three years of screening 489 000 healthy middle aged men to recruit 3 810 men aged 35-49 with cholesterols over 265 and LDL levels greater than 190 mg/dL, hardly a representative population. Nevertheless, it was implied that women and men in other age groups would obtain similar benefits. The trial directors found various ways to hype the benefits and minimize dangers like increased suicides and violent deaths in the treatment group, and using a placebo that had increased GI side effects. Other flaws too numerous to list here such as lowering the standards for statistical significance have been documented by Ravnskov [23]. Leading authorities were outraged by all the ballyhoo and hype, which the eminent nutritionist George Mann summarized as follows [24]:

“They have held repeated press conferences bragging about this cataclysmic break-through, which the study directors claim shows that lowering cholesterol lowers the frequency of coronary disease. They have manipulated the data or reached the wrong conclusions . . . .The managers at NIH have used Madison Avenue hype to sell this failed trial in the way the media people sell an underarm deodorant.”

A similar primary prevention study in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia using gemfibrozil reported a 34 % reduction in nonfatal infarcts and deaths from heart disease deaths [25]. The actual risk reduction was 1.4% and the treatment group had more deaths and a 500 % relative risk increase in basal cell carcinoma. Neither study was of much practical value as both drugs had significant side effects that outweighed their meager benefits. Things changed dramatically with the advent of statins, which were not only more potent, but were also considered to be much safer.

The advantages of statins were exploited and exaggerated in promotional material, which is why Lipitor (atorvastin) became the most profitable drug ever, with well over $131 billion in sales. Lipitor advertisements featured a photo of Dr Robert Jarvik stating that “Lipitor reduces risk of heart attack by 36%* and Lipitor lowers bad cholesterol 39-60%.* It lowered mine.” This relative risk figure suggested that out of 100 people, 36 could avoid a heart attack by taking Lipitor. The asterisk refers to the following in mice type at the bottom of the ad: “That means in a large clinical study, 3% of patients taking a sugar pill or placebo had a heart attack compared to 2% of patients taking Lipitor.” In other words, the actual risk reduction was 1%, so Lipitor would benefit only 1 in 100 rather than 36, and it is not known if that patient would be you. In addition, this was after taking Lipitor daily for 14 years and only in “patients with multiple risk factors for heart disease.”

Jarvik is represented as the inventor of the artificial heart and an authoritative cardiologist, who takes Lipitor and recommends it to family and friends. The advertising blitz, which started in March 2006, started with a fake TV commercial in which Jarvik says, “I'm glad I take Lipitor, as a doctor and a dad. Lipitor is one of the most researched medicines. You don’t have to be a doctor to appreciate that!” The commercial ends with Jarvik sculling off expertly in a very vigorous muscular fashion across a serene lake.

The problem is that Jarvik did not invent the artificial heart, was not taking Lipitor, has never been licensed to practice medicine, and has never sculled; the shots were of double with an impressive middle-aged physique and an accomplished sculler. The close up frames showing Jarvik were taken in a rowing apparatus on a platform to conceal that it was on dry land. Much of the $258 million Pfizer spent on Lipitor advertising from 2006 to September 2007 was for the Jarvik campaign, but it was a good investment.

Thousands of patients taking other brands asked to be switched to Lipitor and 20 % of patients taking less expensive generic statins said they would ask their doctor to prescribe Lipitor. Two thirds said the ad implied that leading doctors preferred Lipitor and many believed that Jarvik regularly treated patients. Numerous complaints prompted a congressional investigation, which revealed that Pfizer agreed to pay Jarvik a minimum of $1 350 ooo for two years to serve as a pitchman, with additional stipends to family members. While there was nothing illegal about this, all promotions featuring Dr Jarvik were withdrawn in 2008 because they created “misimpressions”.

As will be seen in Part 3, after Lipitor lost its patent protection in 2011, Crestor (rosuvastatin) became the best-selling statin brand due to aggressive but equally deceptive advertising articles authored by leading authorities with numerous conflicts of interest. The focus had now shifted from lipids to inflammation as the cause of atherosclerosis and treatment was targeted to lowering C-Reactive Protein (CRP) rather than LDL. The FDA had approved Crestor in 2010 "to reduce the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction and arterial revascularization procedures " in men over 50 and women over 60 with a CRP ≥ 2 mg/L, and the presence of one additional risk factor, such as low HDL, smoking, a family history of premature coronary heart disease or hypertension. This greatly expanded the number of healthy individuals eligible for statin therapy. In addition, statins were portrayed as a panacea that could prevent or benefit cancer, Alzheimer's and numerous other diseases they were more likely to cause. The reasons for this apparent paradox will be explained and we also discuss the impending menace of PCSK9 monoclonal antibody Inhibition, apheresis and other expensive and possibly dangerous therapies designed to lower LDL. As Santayana warned, “Those who do not learn from the mistakes of history are doomed to repeat them,” so stay tuned!

Article first published 29/06/15

Got something to say about this page? Comment

There are 1 comments on this article so far. Add your comment above.

dhinds Comment left 29th June 2015 23:11:03

The only logical conclusions I could derive from Part II of Paul Roach's monologues are: 1.- processed food is unhealthy; 2.- Governmental policies have been manipulated by corporate interests; and 3.- The author is not a vegetarian. What is not yet clear is where he intends to take these long exposures of Science in the Corporate Interest and what he intends to propose in it's place.