The Stern Report commissioned by the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown shows that doing nothing to mitigate climate change will cost us at least five times as much as if we start to act now, but will any government take heed? Prof. Peter Saunders

Almost everyone now accepts that climate change is already happening, that it is going to get worse and that the main cause is the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases we have been spewing into the atmosphere in increasing amounts since the Industrial Revolution [1] ( Global Warming Is Happening , SiS 31). More importantly, almost everyone agrees that we really must start to reduce greenhouse gas emissions immediately [2] ( Which Energy? ).

There are many ways to cut emissions. Some are comparatively cheap and can be done quickly once we decide to go ahead, such as insulating our houses and not cutting down the rain forests. Others are expensive, or will take a long time to put in place, or will require changes in the way we do things. Governments will have to be convinced that these measures are necessary and cost-effective before they adopt them as policy. Furthermore, because climate change is by its very nature a global problem, there will have to be international agreement about what should be done and who should pay for it, even though individual countries, or individual states in the USA, can make a start on their own. So we need a clear idea of what the proposed measures will cost and what they will accomplish.

In July 2005, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, commissioned Sir Nicholas Stern, an economist who was Senior Vice-President of the World Bank from 2000 to 2003, to undertake a review into the economics of climate change .

Sir Nicholas and his panel have now produced a document several hundred pages long that goes into all aspects of the problem: scientific, economic and political [3]. It is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in climate change. An immense amount of data has been assembled together. The analysis and predictions, and recommendations that follow, are the most authoritative we are likely to have for some time.

The Report contains far too much to summarise, and should be read in its entirety. Its main message, however, is stated clearly and succinctly in the five key questions the panel set themselves when they began (Box 1) and the conclusions they reached at the end of their work (Box 2). Climate change is real, and whatever we do now, it is going to get worse, as the effects of past emissions of greenhouse gases work through the system. But if we act decisively and start immediately, we can keep the consequences to well within what we can live with, and at a price we can afford. If we do nothing, or if we delay too long, then not only will the costs rise sharply, the change may be very large and irreversible and the damage very great indeed.

Box 1

Box 2

We need to set the target and work towards it now

The key recommendation of the Report is that we should aim to stabilise the concentration of greenhouse gases (see Box 3) in the atmosphere in the range 450-550ppm. This is higher than the present level of 430ppm, which is in turn higher than the level of only 228ppm before the Industrial Revolution. For that to happen, emissions must peak within the next 10 to 20 years and then fall at a rate of 2 percent a year. By 2050, they must be about a quarter less than they are now. What is more, because the world economy is expected to expand, the rate per unit of GDP will have to be much lower, perhaps only a quarter of the current level.

Box 3

A greenhouse or a conservatory is generally considerably warmer than its surroundings, even if it is not heated. This is because the glass allows the radiation from the sun to pass through with very little loss of energy, but at the same time it prevents most of the heat from escaping

The Earth's atmosphere acts in a similar way, allowing more energy to enter in the form of solar radiation than can escape as heat. It also turns out that if we increase the concentration of certain gases in the atmosphere, then the Earth retains more heat, just as a greenhouse does if you install double-glazing. The most important of these gases are carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulphur hexafluoride and hydrofluorocarbons.

The concentration of the greenhouse gases is usually expressed in parts per million of carbon dioxide equivalent

(ppm CO2e), which means the concentration of CO2 that would produce the same greenhouse effect as the actual mixture that is observed. For example, as methane has a global warming potential 23 times that of CO2 , 1 ppm methane counts as 23 ppm CO2e. Even though methane is a more powerful greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide is used as the reference because there is so much more of it in the atmosphere. In 2005 about 77 percent of the CO2e emissions was CO2 and about 14 percent methane.

For the same reason, annual emissions are generally measured in gigatonnes (billions of tonnes) of carbon dioxide equivalent per year(GtCO2e/y). The global greenhouse gas emissions in 2000 were 42 GtCO2e.

The panel concluded that to allow the level to rise above 550ppm CO2e would substantially increase the risk of very severe impacts without much reduction in the cost of mitigation. To aim for a lower target would be very expensive, and besides it may already be too late.

Furthermore, unless we are prepared to see the concentration of greenhouse gases rise indefinitely, with all the consequences both known and unknown that would entail, we must sooner or later reduce our emissions to below the Earth's capacity to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. This is only 5 GtCO2e/y, about an eighth of the present rate. The longer we delay, the higher the level at which the concentration will stabilise and the more the climate will change; and the measures we take will have to be much more drastic than if we start right now.

The panel estimate that by 2050 the annual cost of stabilisation at 550pm CO2e is likely to be no more than 1 percent of global GDP, i.e. roughly US$1 trillion. They expect it should remain much the same after that, though that will naturally depend on what sorts of new technologies are developed. Over the period 1965-99 the annual growth rate in global GDP was over 3 per cent, so they expect that diverting 1 per cent into mitigating the effects of climate change should only slow the growth of the world economy, not reverse it.

In contrast, on the “Business as Usual” (BAU) path, a conservative estimate of the loss to global world output by the end of the century would be 5 percent of global GDP. The panel conclude that the net benefit of action, i.e. the excess of benefits over costs, would be of the order of $2.5 trillion (present value) and that figure will increase in time. This shows what a good investment we will be making.

There is, of course, more to life than economics and GDP , and there is always a danger in this sort of modelling that we will ignore many of the things that matter the most. One practice is to assign monetary values to some of these things, but this is problematic at best and raises all sorts of moral issues. As the Report states, “A toll in terms of lives lost gains little in eloquence when it is converted into dollars; but it loses something, from an ethical perspective, by distancing us from the human cost of climate change.”

The panel did investigate the cost of including other effects on the quality of life by making conservative estimates of the “ non-market impact s” , i.e., direct impacts on the environment and human health, and found it raised the ir estimate from 5 percent of global GDP to 11 percent . Even allowing for all the uncertainty – one should rather say especially allowing for all the uncertainty – that makes the 1 percent cost of mitigation a real bargain.

You might think that if the cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions is so much less than the cost of doing nothing, the operation of the market should solve the problem for us more or less automatically.

It's not that simple . Markets not very good at looking several years ahead, and carbon emissions, like other kinds of pollution, are what economists call an ‘externality', a cost not borne by the people who benefit from the activity that causes it.

When we use fossil fuels, we pay for the cost of getting the fuel out of the ground and bringing it to where we want it and in a form we can use it. We do not, however, pay for our contribution to global warming. We leave that to everyone else, including the vast majority of the world's population who use far less fossil fuel than we do. That amounts to a substantial subsidy for fossil fuel. In considering the economics of climate change we need to know how big that subsidy is, and the measure commonly used is the ‘social cost' of carbon, the amount of future damage that will be caused by the emission of a tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent today.

The social cost of a tonne of emissions depends on our estimate of damage that will occur many years from now. Over and above the usual problems of making predictions about the distant future, this depends on the level at which the greenhouse gases are stabilised, because the higher the level, the more damage an additional tonne will cause. And that in turn depends on what measures, if any, we have put in place to mitigate climate change.

The result is that estimates of the social cost of carbon can vary considerably. The Report does not arrive at a firm figure, but on the basis of what the panel describes as preliminary work, they estimate that if we aim for the recommended target of no more than 550 ppm CO2e, the social cost of carbon would start in the region of $25-30 per tonne, increasing in time as the concentration of greenhouse gases increases and, with it, the effect of adding one more tonne. The figure of about $25 per tonne is already higher than some other estimates, as the latest scientific evidence warns us that global warming will be greater than was previously thought.

In contrast, if the world were to stay on the BAU path, the Report estimates that the social cost would be about three times as much.

The social cost of carbon is not the same as the price at which carbon emissions are likely to be traded, although over time the two are likely to converge. It is an important figure to know when we are discussing policy, but we cannot solve the problem simply by taxing every activity by the social cost of the emissions it produces.

For example, using the figures given in the Report, the social cost of a gallon of petrol works out to be 31 cents. Yet we know from experience that a rise as small as that would have very little effect on the consumption of petrol. Road transport is a prime example of how we can be so locked into a technology that market forces cannot bring about the necessary changes. Stern suggests that petrol and diesel should be included in emissions trading schemes. This would go some way towards limiting the total fuel consumption because the more petrol was used the more the cost would rise, but it is highly unlikely to be enough to deter people from using fossil fuels.

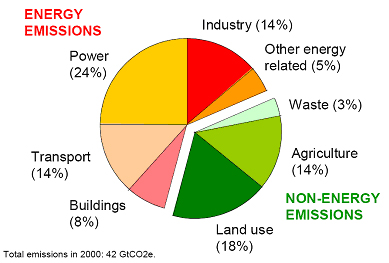

An obvious first step in reducing our greenhouse gas emissions is to know where they come from. In 2000 the total global emissions amounted to 42 GtCO2e and the proportions arising out of different human activities are shown in Figure 1, taken from the Stern Report.

Figure 1. Global carbon emissions by source in 2000

Note that the proportions for Industry and for Buildings represent only direct emissions, e.g., from industrial processes or fossil fuels used for heating; they do not include those activities' shares of the emissions from generating the power that they use. Aviation accounts for about 1.6 percent of emissions but has a greater impact on global warming because the gases are emitted at high altitude. It is estimated that if we follow the BAU path, by 2050 aviation will account for only 2.5 percent of global emissions but 5 percent of the total warming effect.

A striking feature of the pie chart is that a fifth of all greenhouse gas emissions come from changes in land use. Almost all of that is associated with deforestation. The report points out that putting a stop to deforestation could reduce emissions by about 8 GtCO2 e/y at a cost of less than $5/tCO2e, possibly as little as $1/tCO2e. Large scale planting of new forests could save an additional 1 GtCO2e/y for between $5/tCO2e and $15/tCO2e. Both are well below the social cost of carbon.

Further savings could be made at relatively low cost by changing tilling practices, by producing biogas from animal and other organic wastes and by reducing the wastage in the production of fossil fuels and other industrial processes.

The total savings could be of the order of 5 GtCO2e/y.

On the energy side, the first step is to improve energy efficiency. Stern estimates this could reduce carbon emissions by up to 16 GtCO2e/y by 2050. He also considers that fossil fuels will remain a major source of energy and that carbon capture and storage (CCS) may have a key role to play. If all projected fossil fuel plants used CCS, it could save 17 GtCO2e/year at a cost of between $19/tCO2e and $49/tCO2e. He acknowledges, however, that there remain many uncertainties about cost, practicability and the effect on the environment.

Stern discusses in some detail the many other sources of energy that are being developed: on - and offshore wind, wave and tidal, solar (both thermal and photovoltaic), the use of hydrogen for heat and transport, nuclear (if the waste disposal and proliferation issues are dealt with), hydroelectric, and fuel from energy crops (though not if these compete with food crops or forests for land and water). He points out that some of these, while still relatively minor, are growing rapidly. For example the market capitalisation of solar companies grew thirty-eightfold to $27 billion in the 12 months to August 2006.

Stern also reminds us that many of the measures necessary for mitigating climate change have other benefits as well. Energy efficiency, for example, reduces costs and contributes to energy security. In Europe, the measures required to limit climate change to 2°C would lead to savings of €10 billion per year on existing air pollution control and €16-46 billion on avoided health costs. Moreover, if we are concerned about the loss to the economy if high emissions activities are curtailed, we must not ignore the gains from the new industries that will be developing. Even in the USA, where the greatest fears have been expressed about the economic consequences of action against climate change, clean technology had already become the third largest category of venture capital investment by the second quarter of 2006.

If we could agree about the measures we should take , t hat still wouldn't tell us how we can make them happen. Governments have direct control over only a comparatively small fraction of what goes on in a country. What they can do is to set targets, pass laws, impose regulations, raise or lower taxes and give or withdraw subsidies, and it is not easy to devise measure s t hat will bring about significant reductions in emissions without doing too much collateral damage.

This is made even harder by the global nature of climate change. Any single government is naturally reluctant to take unpopular measures that the other governments are not taking, and especially to put its own industrialists and farmers at a serious competitive disadvantage. Stern points out, however, that the effect is less than is often supposed. For many industries, the extra costs would not be large enough to warrant a move, especially if they can reduce their emissions by using new technology, which often has other advantages as well. And on the whole, the industries that produce very large emissions are not easily transferable from country to country.

Stern considers that carbon pricing and emissions trading will be very important in reducing emissions, but points to a number of difficulties that have to be overcome. For example, if the initial allocations are not free, or if the total to be allocated is significantly less than the current level, the transition may be very difficult as firms will be faced with a sudden large cost that they have no time to mitigate. On the other hand, if the initial allocations are free and do correspond to the current level, as has been the case in the EU, there is very little incentive for anyone to cut back. What is more, new firms, who will have to purchase allocations for their emissions, will be at a competitive disadvantage, yet it is precisely these that we want to encourage because they are more likely to be using new, low emissions technology. If we try to help them by adopting a “use it or lose it” policy to stop older firms hoarding allocations, the result may simply be that old, inefficient plant is kept in operation at the expense of better technology.

New technology is seldom as cost efficient when new as it will become after a few years. Think of how much more you get for your money when you buy a PC now compared with twenty years ago. Unfortunately, as Stern points out, while computers were able to establish a market and then develop, the nature of many important sectors such as power generation makes this unlikely to happen without assistance. The old technology also has the advantage of an existing infrastructure that has been designed to suit it. For example, large investments have gone into systems for moving electricity, gas and goods (including food) over considerable distances. This can make it harder for local production to grow to the point where economies of scale make it cheaper as well as more carbon efficient.

Stern recommends that “deployment incentives” for low emission technologies should be increased two to five times globally from their present levels of around $34 billion. He also recommends that global public energy research and development funding should be doubled to about $20 billion.

It is already too late to stop climate change completely, and Stern recommends that we should aim to stabilise the greenhouse gas concentration at 550ppm CO2 e. Even if we achieve that, however, it is expected that the mean temperature on the Earth will rise by at least 2°C. That will have serious enough effects. For example, the sea level will rise, many areas will have a greatly reduced supply of water, and there will be many more extreme weather events such as hurricanes.

No matter what we do to mitigate climate change, we will also have to devote resources to adapting to the change that does occur. We must also expect a loss in agricultural productivity that will get worse as the temperature increases. What is more, because most of the areas that will suffer the greatest are in the developing world, there will have to be international cooperation, with the rich countries making substantial contributions.

The main message of the Stern Report is that we can do quite a lot about climate change. It's too late to stop it altogether but we can limit global warming to no more than about 2°C and we can cope with the damage that will cause. What is more, we can do both at a price we can afford, say 1 percent of the world's current total consumption.

But we have no time to lose. The longer we put it off, the harder it will be, the more it will cost, the less it will achieve, and the higher the risk that that the effect will be both irreversible and so great that we will not be able to deal with the consequences in any reasonable way.

Keeping climate change within bounds is going to require governments to act quickly and decisively. It will also require international cooperation on an unprecedented scale. Countries are going to have to sign up to and abide by agreements that will imply considerable changes in the way they do things. The rich countries are going to have to pay a bigger share of the costs, including a major contribution to helping the developing countries to adapt to those changes that do take place, but not to the extent that it will have a significant effect on their own economies.

As for the individual citizen in the developed world, the good news is that our own quality of life need not suffer. The estimated 1 percent of GDP will mean not that our standard of living will fall but only that it will rise more slowly than if we were ignoring the problem. We'll find ourselves doing less of some things, like flying to faraway countries for the weekend. We'll do other things in different ways: we'll heat water using solar energy and we'll probably go to work on efficient public transport instead of driving alone in an SUV on a crowded road. But on the whole we'll live just as well as if we weren't doing anything about climate change. The difference is that we won't be doing it at the expense of our grandchildren.

For more options on what we can do, read ISIS' Which Energy? [2] .

Article first published 16/01/07

Got something to say about this page? Comment