White non-Hispanic American men and women aged 45-54 are getting sicker and dying at increasing rates since 1998, in striking contrast with other age and ethnic groups in the US and the same age group in other industrialized countries, which have seen both rates of illnesses and death consistently falling over the same period Dr. Mae-Wan Ho

The death rate among middle-aged white Americans is rising in a striking reversal of decades of longevity gains. This startling finding is revealed in a new study published by two American professors of economics at Princeton University, New Jersey. The increase in death rates is paralleled by self-reported declines in physical and mental health, ability to conduct activities of daily life, and increases in chronic pain and inability to work, as well as clinical deteriorations in liver function [1] “all pointing to growing distress in this population.”

One of the authors Angus Deaton is the 2015 Nobel laureate in economics. He told the Washington Post that drugs and alcohol and suicide are clearly the proximate cause. “Half a million people are dead who should not be dead,” he said [2]. “About 40 time the Ebola stats. You’re getting up there with HIV-AIDs.”

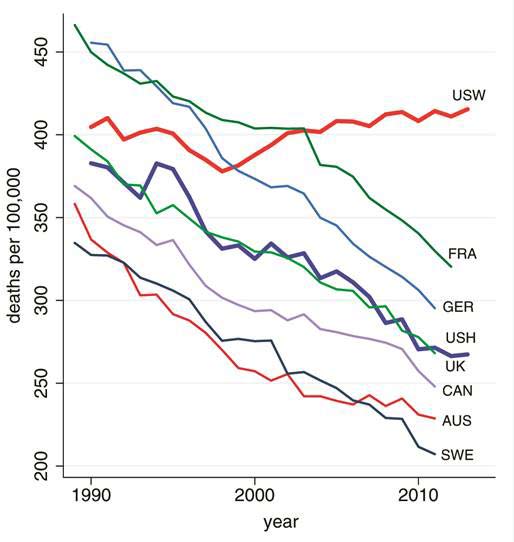

What makes it so dramatic and mysterious is that the finding is specific to middle-aged white non-Hispanic Americans, and not any other age or ethnic groups in the US. Thus, the same age group among US Hispanics and six other rich industrialized countries - France, Germany, UK, Canada, Australia and Sweden - all show a consistent downward trend since 1990 and before (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 All-cause mortality among 45-54 age group in US non-Hispanic whites compared with US Hispanics and six other rich industrialized nations

Three causes of death account for the trend reversal mong middle-aged Whites. Poisoning due to drugs (including alcohol) tops the list with the steepest increase followed by suicides and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis; all increasing since 1998.

The trend reversal was primarily due to the increase in all-cause mortality among those with the lowest educational level – high school degree or less – increasing by 134 per 100 000 between 1999 and 2013; those with college education less than a saw little change over the period; while those with a BA or more saw death rate fall by 57 per 100 000. Although mortality from suicide and poisoning increased in all three educational groups, the increases were largest in the group with the least education.

In measures of self-assessed health status, there was a large and statistically significant decline in the fraction reporting excellent or very good health (6.7 %) and a corresponding increase in fraction reporting fair or poor health (4.3 %). The increase in reports of poor health was in turn matched by increased reports of pain: neck pain, facial pain, chronic joint pain and sciatica. One in three white non-Hispanics aged 45-54 reported chronic joint pain in the period 2011-2013; one in five reported neck pain, and one in seven reported sciatica. These represent an additional 2.6 % reporting sciatic or chronic joint pain since 1997-1999, an additional 2.3 % reporting neck pain, and an additional 1.3 % reporting facial pain.

The fraction reporting serious psychological distress also increased significantly, rising from 3.9 % to 4.8 % over the same period.

Over the same period, there was a 2 to 3 % increase in people reporting having more than a little difficulty in ability to cope with daily living activities, such as walking a quarter mile, climbing 10 steps, standing or sitting for 2 h, shopping, and socializing with friends; the fraction reporting difficulty in socializing – a risk factor for suicide – increased by 2.4 %.

In total, people reporting that their activities are limited by physical or mental health increased by 3.2 %. The fraction reporting being unable to work doubled for the middle-age white non-Hispanics in this 15 year period.

Risk for heavy drinking – more than one or two drinks a day – also increased significantly.

The increased availability of opioid prescription drugs that began in the late 1990s has been widely noted, as well as the associated mortality. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that for each prescription painkiller death in 2008, there were 10 treatment admissions for abuse, 32 emergency department visits for misuse or abuse, 130 people who were abusers or dependent, and 825 nonmedical users. In the period of study, the US saw falling prices and rising quality of heroin, as well as availability in areas where the drug had been previously largely unknown.

“The epidemic of pain which the opioids were designed to treat is real enough,” the authors write [1], “although the data here cannot establish whether the increase in opioid use or the increase in pain came first. Both increased rapidly after the mid-1990s.” Pain is a risk factor for suicide; and increased alcohol abuse and suicides are likely symptoms of the same underlying epidemic.

“Although the epidemic of pain, suicide, and drug overdoses preceded the financial crisis, ties to economic insecurity are possible.” The authors suggest [1]: “After the productivity slowdown in the early 1970s, and with widening income inequality, many of the baby-boom generation are the first to find, in midlife, that they will not be better off than were their parents.” While the same slowdown in productivity occurred in other industrialized nations, the authors point out that the US has moved primarily to defined contribution pension plans with associated stock-market risks, in Europe, defined-benefit pensions are still the norm, and therefore, future financial insecurity may weigh more heavily on US workers.

A serious concern is that the currently midlife will age into Medicare in worse health than the currently elderly; they may be [1] “a “lost generation” whose future is less bright than those who preceded them.”

Other commentators agree. A sicker population will place an increasing burden on society and federal programs. [2]

“This is the first indicator that the plane has crashed,” said Jonathan Skinner, a professor of economics at Dartmouth College who reviewed the study and co-authored a commentary that appears with the article. “High school graduates [and] high school dropouts [are] 40 % of the population.” Skinner added [2].

Article first published 16/12/15

1. Case A and Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white n0n-hispanic American in the 21st century. PNAS Early Edition, www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1518393112

2. “A group of middle-aged whites in the U.S. is dying at a startling rate”, Lenny Bernstein and Joel Achenbach, The Washington Post, 2 November 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/a-group-of-middle-aged-american-whites-is-dying-at-a-startling-rate/2015/11/02/47a63098-8172-11e5-8ba6-cec48b74b2a7_story.html

Comments are now closed for this article

There are 3 comments on this article.

Rory Short Comment left 17th December 2015 08:08:03

The USA is often the front runner in life style issues, let us hope not in this case.

Todd Millions Comment left 22nd December 2015 10:10:37

I am alarmed and warned but- The Canadian line: We just had a Federal election. Elections Canada had all my info bollixed yet not canceled .It seems I was dead!Moreover I died in a province I've never being too.Which is more alarming.The Dead voting liberal in Canada is not at all unusual. We have in fact, ended up with several Prime Ministers due to this- extreme party loyalty. The line representing Canadian mortality may therefore have too be flattened some what to adjust for this.I would not advise trusting health or statistics Canada to do this.

I would also think the American factor as to how many hospitalized organ donors end up dead just as a tissue match is required should be looked at.

susan rigali Comment left 29th December 2015 04:04:08

By the 1950s, the predominant attitude to breastfeeding was that it was something practiced by the uneducated and those of lower classes. The practice was considered old-fashioned and "a little disgusting" for those who could not afford infant formula and discouraged by medical practitioners and media of the time.[19] Letters and editorials to Chatelaine from 1945 to as late as 1995 regarding breastfeeding were predominantly negative.[19] However, since the middle 1960s there has been a steady resurgence in the practice of breastfeeding in Canada and the US, especially among more educated, affluent women.[19]