Belated, good in parts, but not green and definitely lacking in vision. Prof. Peter Saunders and Brett Cherry

The world is shifting to renewable energies in the wake of peak oil and accelerating global warming. Contrary to exhausting supplies of fossil and nuclear fuels, renewable energy is inexhaustible energy. In 2008, more capacity in renewable energies has been added than conventional, and the trend is continuing, with many politicians and experts considering 100 percent renewable by 2050 a distinct possibility [1] (see Green Energies - 100% Renewable by 2050, I-SIS publication). The German government, for one, appears to have made 50 to 100 percent renewable energy by 2050 its target [2] (Germany 100 Percent Renewables by 2050, SiS 44)

The UK has lagged far behind. It is trailing the EU league for renewables, being third from bottom ahead of Luxembourg and Malta [3]. UK received 1 percent of its energy from renewables in 1995; that increased to 1.3 percent ten years later in 2005, and is currently about 1.8 percent.

The UK government’s White Paper [4] is a belated attempt to salvage the situation by taking on board the message of the Stern Report [5, 6] (see The Economics of Climate Change, SiS 33) including the positive finding that mitigating climate change is not only possible but affordable.

The short term aim is that by 2020 the UK’s emissions should be reduced by 18 percent from the 2008 level, a larger reduction if the Copenhagen summit agrees appropriate international targets. By 2050, emissions are to be cut by 80 per cent from 1990 levels, a target recommended by the Independent Committee on Climate Change as the UK’s contribution to halving global emissions by 2050.

A separate report, The UK Renewable Energy Strategy 2009 [7] from the Department of Energy and Climate Change sets out a path to a “legally binding target” of 15 percent of UK’s energy from renewables by 2020, reducing 750 Mt CO2 by 2030, and decreasing UK’s overall fossil fuel demand by around 10 percent and gas imports by 20-30 percent. A £100 billion new investment will create 500 000 jobs in the renewable energy sector.

The White Paper [4] contains a great deal of detail on how the targets are to be achieved. There is a long list of measures (see Box 1) for producing low carbon energy and for reducing energy consumption, and a long appendix giving the savings that each is supposed to contribute. There is to be an EU-wide carbon trading scheme with a total that reduces year by year. There is to be support for energy conservation, for the development of renewable energy sources, for measures to reduce emissions from farms, for the creation of more woodland to remove CO2 from the atmosphere, and more. That’s the good news.

Box 1

Key proposals· All major Government departments have been allocated their own carbon budget and must produce their own plan

· About 30 percent of electricity to come from renewables by 2020

· Up to four demonstration coal burning power plants with carbon capture and storage

· Facilitate the building of new nuclear power stations

· About £3.2 billion to help households become more energy efficient; smart meters in every home.

· People and businesses to be paid for generating electricity from low carbon sources

· Assistance to low income groups

· Support development of green industry including up to £120 million investment in offshore wind and £60 million for marine energy

· A 40 percent cut in average CO2 emissions from new cars in EU. Support for new electric cars.

· A framework for tackling emissions from farming

· A “smart grid”

The bad news is that there will be great reliance on carbon capture and storage and on nuclear power; both not renewable, not sustainable and not green (see Chapters 3-7, 9, 10 in [1]). The Government will seek an agreement on including international air and sea transport into the national emission totals, but there is nothing about taxing aviation fuel, or plan to reduce air travel.

The basic principle underlying the White Paper is “Business as usual, only smarter”. We will unplug our old fossil fuel and nuclear power stations from the grid and plug in new, hopefully better ones. We will continue to rely heavily on private transport, though with cars that emit less CO2 per mile. There will be at least as much air travel in 2050 as today, though in more efficient aircraft. And so on.

Life was very different 50 years ago and it will be very different 50 years from now. It will have to be, if our descendents are to live well and yet produce only a tiny fraction of the greenhouse gases that we do. In a White Paper that claims to look 50 years ahead, there is remarkably little in the way of forward planning to avoid committing our successors to a life style that’s essentially the same as ours. Many crucial things like the design of our cities and major infrastructure such as railways take a very long time to change, and if they are to be ready for 2050 the planning has to start now.

Within the EU, a carbon trading scheme allows some flexibility while the total emissions are being reduced (see Box 2). The White Paper, however, anticipates that rather than driving through all the emissions cuts to which it has committed itself, the UK will purchase credits “that will deliver emissions reductions in developing economies.” In other words, the UK will reduce its carbon emissions by less than it has agreed to and the developing countries will reduce theirs by more.

Box 2

What is carbon trading?The principle of carbon trading is that a central body, such as a government or an international organisation, sets a limit, or ‘cap’, on the total amount of greenhouse gases (GHGs) that can be emitted. Companies buy or are given credits that allow them to emit given amounts of GHGs. If they want to emit more GHGs than they have credits for, they can buy them from companies that intend to emit less than their allowances.

The EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) is the largest system of this kind but it will still cover only 45 percent of the EU’s emissions. There are a number of criticisms of the EU ETS.

· Countries can offset their carbon emissions by purchasing other countries’ unused carbon allowances, resulting in little if any real reduction in total carbon emissions; when offset is done in developing countries as the UK White Paper intends, it effectively places extra burden on developing countries to reduce their emissions [8]

· In the first phase, generators benefited from windfall profits by passing the notional cost of carbon permits onto customers even though they had paid nothing for them. The customers may have to pay again when carbon allowances are no longer free for generators from 2013 [9].

· The EU ETS is concerned only with carbon dioxide and does not include other important GHGs such as methane and nitrous oxide [10].

· The data set used by the EU ETS does not extend back before 2005 with the result that some countries are likely to receive over-allocations of carbon credits [11].

· If carbon trading is to be effective, the price of carbon needs to be at a level that encourages countries to reduce emissions while also promoting new technology. In general, carbon trading schemes advantage old companies over new entrants, yet it is the latter that are more likely to be employing low carbon technology [6].

The effect could be very large indeed. About 70 percent of UK emissions come from industrial sectors that are within the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and the Government does not propose to limit the number of credits that can be bought to meet the reduction target for this sector. Only that can explain why the Government can issue a White Paper detailing the swingeing cuts in emissions that are going to be required and at the same time give the go-ahead for a third runway at Heathrow and at least four new coal-fired power stations without CCS [11].

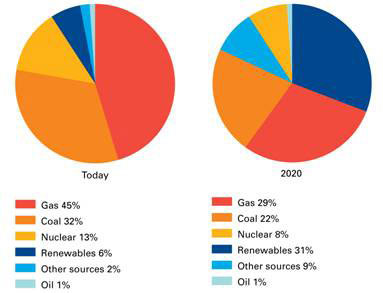

At present, about 45 percent of our electricity is generated from gas and about 32 percent from coal. (See Fig. 1). The White paper estimates that in 2020, those figures will still be 29 percent and 22 percent respectively. The Government is placing great reliance on carbon capture and storage (CCS) in which the carbon dioxide produced in burning fossil fuels is captured and transported to an underground repository such as a depleted oil field. As the White Paper itself admits, this has never been tried on a commercial scale, and while the three stages have each been shown to work, the process as a whole has not [12] (see Carbon Capture and Storage A False Solution, SiS 39)

Figure 1 UK’s planned transition to low carbon electricity generation

The new Department of Energy and Climate Change is to support up to four demonstration plants, and as other countries are going to build them as well, the Government is confident that a way will be found to make CCS safe and economical on the scale required. If not, it is hard to see how the targets will be met, because there is no plan B.

If CCS does work, there will be increased worldwide demand for fossil fuels; thereby hastening the arrival of peak gas and coal in addition to oil, especially because the CCS system is estimated to use up between 10 and 40 per cent of the energy produced by the plants to which it is fitted [12].

NUCLEAR ENERGY

At present, about 13 per cent of our electricity comes from nuclear. This will be reduced to 8 per cent by 2020 because old stations will be decommissioned faster than new ones can be built; the proportion is intended to rise again after 2020 but there is no target figure.

One of the strongest arguments against nuclear power is that it is not economical. The nuclear industry has been notorious for cost overruns during construction of power plants. But that is nothing compared to the downstream costs of decommissioning and waste management and disposal [13, 14] (Nuclear Industry’s Financial and Safety Nightmare and The Nuclear Black Hole, SiS 40). When the Thatcher government privatised the electricity generating industry in 1989, they were unable to sell off the nuclear power stations that were not seen as good investments. The taxpayer had to take over all the liabilities and the costs of running the dirtiest, loss-making parts of the industry at Sellafield, now £3 billion a year and rising. Meanwhile the cost of clean-up and decommissioning has ballooned to over £73 billion. Sellafield has become the world’s nuclear waste dump with no end in sight, its waste reprocessing plants non-functional, and there is as yet no designated final waste repository.

According to the White Paper, “it will be for energy companies to fund, develop and build new nuclear power stations in the UK, including the full costs of decommissioning and their full share of waste management and disposal costs.” That means the Government will build a facility to dispose of the waste from existing plants and the industry will be expected to pay only the extra cost of adding waste from the new ones. The Government has not yet decided how to estimate those costs but it seems likely that the companies will pay a risk premium in return for which there will be an upper limit to what they will be required to contribute. Anything above that limit will be again for the taxpayer to cover.

If we go ahead with nuclear power, our children and grandchildren are likely to find themselves picking up a bill for waste disposal that will make our £73 billion look pretty small beer. They will be burdened with toxic and radioactive wastes of mammoth proportions including those we haven’t been able to deal with.

Safety is decidedly a major issue with nuclear power [15] (Close-up on Nuclear Safety, SiS 40). It turns out that no nuclear power plant, not even the ‘generation 3’ reactors under construction are proof against malfunction or malevolent attacks. In addition, a main source of hazard is spent fuel stored on site in overcrowded cooling ponds before they are shipped out for storage in the final repository. These can easily catch fire and cause explosions. Sellafield has been declared “the most hazardous place in Europe” by its deputy managing director [16], and a “slow motion Chernobyl” by Greenpeace.

The fallout from Chernobyl was 30 to 40 times that released by the atom bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan during World War II. A 2005 report attributed to Chernobyl 56 direct deaths and an estimated 4 000 extra cancer cases among the approximately 600 000 most highly exposed, and 5 000 among the 6 million living nearby [17].

There is also strong new evidence from Germany linking childhood leukemia and proximity to nuclear power stations, This gives a hint on the health burdens of accumulating toxic and radioactive wastes from the nuclear industry to present and future generations.

But the White Paper persists in dismissing such evidence, as the UK Government has been doing for years (see Box 3).

Box 3

Childhood cancers linked to nuclear power stationsFor years there have been conflicting reports about whether the incidence of childhood cancers, especially leukaemia, is higher in the vicinity of nuclear power stations. As the numbers are small it can be difficult to decide whether an observed cluster represents a real effect or merely due to chance [18].

Now research commissioned by the German Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz (BfS, Federal Office for Radiation Protection) [19, 20] found a significantly increased incidence of leukaemia in children living within 5 km of a nuclear power plant, and a smaller but still significant increase in children living between 5 km and 10 km. They also found a statistically significant regression coefficient between the increased incidence of leukaemia and distance from the power station; this correlation is more compelling evidence than the existence of clusters. Their conclusions have been confirmed in a recent detailed analysis [21]

But the UK Government dismissed this evidence in its White Paper [4] on the grounds that the correlation does not prove that ionising radiation emitted by German nuclear power stations was the cause of the leukaemia. It also stressed that the report of the UK Committee on Medical Aspects of Radiation in the Environment (COMARE), which found no link, was based on a considerably larger number of cases, but did not mention that the BfS report was based on a “case-control” study in which each information such as the distance from the home to the power station was known exactly for each child in the study [22].

In fact, while COMARE found no greater incidence of cancer near nuclear power stations, it did find a greater incidence near the nuclear installations at Sellafield, Aldermaston, and Rosyth.

The UK Government is applying as usual the anti-precautionary principle with regard to childhood cancer and nuclear power stations. This is much the same argument that the tobacco industry used: just because the incidence of lung cancer is higher in smokers and correlated with the number of cigarettes smoked, that does not prove smoking causes lung cancer and there is no need to stop manufacturing and marketing cigarettes.

In principle, the White Paper [4] is encouraging about the future of renewable energy, and the detailed strategy laid out in a separate report [7]. The Government says it will encourage wind power, both onshore and offshore; it will retain the Renewables Obligation and Climate Change levy to encourage investment in renewables, and make it easier to connect to the grid. Feed-in tariffs for renewables will be introduced [7]. It will investigate the possibility of power from the Severn Estuary; it will support anaerobic digestion, and so on. But there is certainly nothing like the enthusiasm expressed by the German Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, which sees renewables as a major industry in Germany and boasts that “Renewables made in Germany” are already highly successful in world markets [23].

Domestic transport is responsible for about a fifth of the UK’s emissions, and the White Paper proposes many measures for reducing this contribution, from electric cars to improving the tyres on heavy goods vehicles. There is a lot on making cars more carbon efficient and some on incentives to move from car to rail or bus or even bicycle. But there is nothing about redesigning our cities to make a car less of a necessity.

It is not easy to make this sort of change, but the White Paper is about the period up to 2020 and looks ahead to 2050. This gives the government the opportunity to introduce long term policies that will make it possible to move away from dependence on car ownership without detracting from the quality of life.

Another disappointing feature is that the government assumes there will be even more air travel in 2050 than today. While there are plans to move traffic from road to rail, the Government seems to have little interest in discouraging air travel. On the contrary, it reiterates the importance of expanding the capacity of Heathrow. Shortly after the White Paper was published, however, plans were announced for a high speed rail service connecting London and Glasgow. We have not heard the last of this debate.

Most of the emissions from farms come either from animals or from fertiliser, and farmers will be shown how to reduce these. The Government does not, however, mean to take this as far as giving additional support to organic farming. This is most disappointing in view of the enormous potential that organic agriculture and localised food and energy systems have for saving energy and mitigating climate change, as documented in our report [24] (Food Futures Now: *Organic *Sustainable *Fossil Fuel Free, I-SIS publication) and updated since [25] (Organic Agriculture and Localized Food & Energy Systems for Mitigating Climate Change, SiS 40).

Climate change is a global problem and needs global solutions. Up to a point, the government is conscious of this. It recognises, for example, the need to have globally agreed targets for the reduction of CO2 emissions and an agreement on how to include international air and sea transport in the total.

But a document that looks forward to 2050 should be thinking more about what the world will be like by then. We will have reached the end of the era in which the relatively few of us in the North have a life style very different from the rest. You only have to visit China or India or many other developing countries to see this change happening. By 2050, what is now the third world will have caught up economically and will be able to pay for oil, coal, gas and even uranium at the same rate that we do, and emit CO2 at the same per capita rate. Buying emissions credits from developing countries is immoral; there will soon come a time when we also won’t be able to afford it.

Parts of the White Paper are, as the curate said, excellent. It makes the case that climate change is real and it commits the UK government to doing something about it. The plan is detailed enough that every sector knows what is expected of it; no one is going to be able to do nothing on the grounds that their contribution to the total is too small to matter.

There are, however, important shortcomings; notably the heavy reliance on nuclear energy, the hazards and the problems surrounding waste disposal very much played down; and carbon capture and storage that has never been properly tested either for safety or for economic viability. .

Most of all, the White Paper is remarkably unimaginative in envisaging a UK in 2050 very little different from today: still relying heavily on fossil fuels, still travelling by air and in private cars, still taking it for granted that as a wealthy country it has first call on the world’s non-renewable resources and will be able to buy all emissions credits it needs, leaving the real reductions to be made by others.

Recent events are making the White Paper obsolete almost before the ink is dry. In the USA, the nuclear power industry has so far failed in its efforts to overturn any ban on building more reactors, and the Obama administration had put a freeze on Yucca Mountain as long-term waste disposal site. Even Canada, which has its own supplies of uranium and its own design of reactor, the CANDU, has put its programme on hold (see Chapter 3 of [1]). The UK Committee on Climate Change told the Government that if air travel is not curbed, the rest of the economy will have to cut emissions by 90 percent rather than the currently expected 80 percent [26]. What’s more, the Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is advising that rather than allow the greenhouse gas level in the atmosphere, currently 385 ppm, to stabilise at 450 ppm, we must reduce it to 350 ppm if we are to avoid irreversible climate catastrophe [27] (350ppm CO2 the Target, SiS 44).

The Government will have to think again, and be both bolder and wiser.

Article first published 05/10/09

Comments are now closed for this article

There are 3 comments on this article.

Bill Hamilton Comment left 13th October 2009 17:05:07

The views expressed in the article concerning the decommissioning of legacy nuclear plants in the UK to do not stand up to any detailed scrutiny. The authors state that the costs of decommissioning are "ballooning". However, if they had read the NDA Strategy published in April 2006 and available on the NDA website they would have seen that the NDa always predicted a bell curve in terms of clean-up costs in that as the organisation got a better understanding of what was there then costs would rise, but then begin to fall as efficiencies of scale and the application of proper project management and technological innovation are brought to bear. A reading of the NDA's Annual Report published in July 2009 would show only a 1% increase in lifetime decommissioning costs over the year showing that the bell curve theory is working out in practice.

Secondly, the article alleges that reprocessing plants at Sellafield are not operational. this is simply not true. These plants have contributed in excess of £1 billion over the past four years that has been used to offset the cost of decommissioning, something else ignored by the authors in their assertions.

andrew fawcett Comment left 15th October 2009 02:02:38

you say that the German government has targeted 50% to 100% of its energy to be renewable by 2050.

OK, which, 50% or 100%???

there is a big difference.

Polprav Comment left 17th October 2009 16:04:04

Hello from Russia!

Can I quote a post in your blog with the link to you?