Fuel-efficient super-clean cars are at our doorstep and they run on methane produced by cleaning up wastes. Dr. Mae-Wan Ho

Chris Maltin arrived with a sunny smile at the Dream Farm workshop organised by I-SIS on a bright, clear Saturday morning in January 2006.

He has driven to the venue at Kindersley Centre in Sheepdrove Organic Farm Berkshire in his Mercedes People Carrier, and was eager to show it off to everybody. It is not just any Mercedes People Carrier, but one specially built to run on methane gas; and not just any methane gas, but methane obtained from treating organic wastes in a special anaerobic digester that Maltin has designed.

Maltin, founder and CEO of Organic Power Ltd., a company based in Somerset, has been keen on anaerobic digestion for many years. “Anaerobic digestion converts biomass directly to useful fuel without any intermediate steps, the conversion efficiency is very high compared to other alternatives such as bioethanol or biodiesel.” He says. “It can handle a variety of wet substrates ranging from green garden waste, septic tank wastes, kitchen waste, energy crops and a variety of other organic materials in industrial byproducts or wastes.” (See “Dream Farm” SiS 27; and “Dream Farm II”, SiS 29.)

There is no loss of nitrogen into the atmosphere, so all the nutrients can be returned to the soil as fertiliser. “And, as the materials digested are organic matter, they can be considered carbon neutral.” He adds.

Figure 1. Organic Power's methane driven Mercedes people carrier

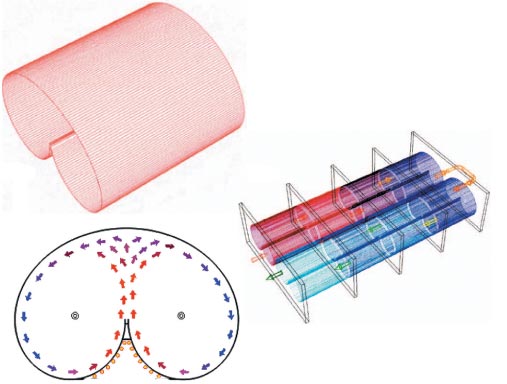

Maltin's improved anaerobic digester is based on his original design, patented as the Maltin System. It consists of eight identical plug-flow units (tanks) horizontally-mounted in series, the tank is shaped in such a way that it maximises circulation within the tank with minimum energy, but there is little or no mixing between the tanks, so that a high efficiency of digestion is achieved (Fig. 2). The digester is maintained in an external temperature controlled lagoon, so it can be made of relatively thin plastic sheet material, and the hydrostatic pressure exerted on the wall from inside the reactor is balanced by the pressure from the outside by the water in the holding lagoon. Heat can easily be supplied to the digester by heating the water in the holding lagoon.

Figure 2. The Maltin System

Wastewater is routinely analysed for chemical oxygen demand (COD) – the quantity of oxygen used in biological and non-biological oxidation of materials as a measure of total wastes or water quality - and Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) - the amount of oxygen taken up by aerobic microorganisms to decompose the organic matter as a measure of water pollution.

The digest, when tested in Professor Charles Banks' laboratory at Reading University, showed that about 50 percent of the COD was removed by the time it reached the last of the eight tanks in series. (This level of waste removal is not exceptional for biogas digesters.) The BOD removal was more impressive, at 99.93 percent. That means the wastewater has been effectively purified from bacterial contamination.

The water is not the only thing that's clean, so is the exhaust from his Mercedes People Carrier.

Maltin is actively involved in the development and supply of gas-fuelled vehicles. The advantage of natural gas is that it has a very much higher octane rating than petrol. The octane rating of a fuel tells you how much it can be compressed before it spontaneously ignites. One way to increase the power of the engine is to increase its compression ratio, so a high performance engine has a higher compression ratio and requires higher-octane fuel.

Hence, a dedicated natural gas engine can incorporate higher compression ratio with higher power output, which also means higher fuel efficiency.

Instead of natural gas, Maltin runs his Mercedes on what he calls “renewable natural gas”, which is almost pure methane from biogas after removing carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulphide. Compared with petrol or diesel, renewable natural gas considerably reduces exhaust noise levels, lowers emissions of nitrogen oxides, and has almost zero emissions of particles or dust. The car has a range of 350 miles.

The exhaust in a gas engine runs hotter and the catalytic converter (device that removers pollutants from motor vehicle exhaust) needs to be a dedicated unit to cope with this and to trap any unburnt methane in the exhaust. Organic Power is working closely with Lubrizol to develop this catalytic converter.

At a sustainable technology fair in Glasgow, Scotland in May 2004, West Lothian Council provided their latest exhaust emissions testing vehicle to test Maltin's Mercedes. Even without a catalytic converter, it had 0.02 percent carbon monoxide (3.5 percent allowed), and 123 ppm particulates ( 1 200 ppm allowed). 1

Organic Power has been lobbying for fuel duty to reflect environmental impact in order to encourage renewable fuels. Sweden, Switzerland and Germany have no fuel duty on renewable natural gas, and Sweden is world leader in gas-powered vehicles (see Box).

The case of Sweden 2

Sweden leads the world in using natural gas as a vehicle fuel and in particular biogas. The population is sparce, so it is difficult to invest in large infrastructure. In the western part of the country, a gas distribution system exists which imports mainly from Denmark. In the rest of the country, methane gas is distributed from a number of biogas plants where methane is produced locally, typically owned and operated by the municipalities. Much growth in the use of natural gas vehicles was achieved through joint ventures between carmakers and bus and taxi companies. There are now around 4 500 natural gas vehicles in Sweden, 40 percent run on biogas. The Swedish Natural Energy Administration have allocated 1.5 m euros for the national organisation and co-ordination of clean biogas or clean natural gas infrastructure development, and the Swedish government has proposed a 20 percent lower taxation on company cars when choosing clean fuel vehicles, and support of 30 percent of the investment in plants upgrading biogas to vehicle fuel. There is permanent tax relief on biogas and a moderate tax level on natural gas. There are more than 230 biogas plants in Sweden and about 130 of these are located at sewage water treatment plants. Sixty percent of the total Swedish biogas production comes from these plants. The other main source (30 percent) is from landfills.

The Swedish Association of Green Motorists has ranked renewable natural gas driven cars the best environmental car for 2005,3 they occupied the first 8 positions of 52 cars tested. The CO2 emission in gram/km ranged from 9 to 14, about one-tenth that of petrol and diesel driven cars. For comparison, two ethanol (E85, 85 percent ethanol blended with petrol) driven cars had emissions of 54 and 69 gram/km.

Some 200 m tonnes of municipal solid wastes are generated each year in the European Community, 4 60 to 70 percent of which is probably organic. In addition, hundreds of tonnes of livestock manure and crop wastes are produced on European farms. Much of this organic waste is going to waste in landfills or incinerators. The UK topped the league of EU nations by sending more than 70 percent of its municipal wastes to landfills in 2003, 5 releasing methane into the atmosphere and poisoning land and water.

Instead of which, the organic wastes could be treated in anaerobic digesters to provide methane for fuel, rich fertilisers for crops, and much cleaner land, water and air.

“Using biogas produced from organic materials in the UK and uprating this to renewable natural gas could provide 20 percent UK's vehicle fuel.” Says Chris Maltin.

Article first published 20/03/06

Got something to say about this page? Comment