Cautionary tale for GM and other control strategies as study highlights expansion of another invasive disease carrying mosquito in Panama Dr Eva Sirinathsinghji

A new study in Panama raises concerns over the strategy of releasing genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes to control diseases.

The study, published in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [1], maps the expansion of the invasive Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, which carries many viral pathogens including Dengue, Yellow Fever and Chikungunya and is also implicated in the transmission of LaCrosse encephalitis virus to humans in the US. Chikungunya virus is native to tropical regions of Africa but is now considered an emerging global pathogen since its detection in non-native regions in 2006. Dengue fever is increasingly common, with global rates rising 30-fold between 1960 and 2010 [2].

Current strategies in dealing with the spread of these diseases focus on another species of mosquito, the Yellow Fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti which has been in the Americas since the 1500s and considered the most common carrier of Dengue as well as Chikungunya and Yellow fever. The study highlights the limitations of strategies such as GM mosquito releases to eradicate disease through failure to deal with other species of mosquito. GM mosquito releases are hence predicted to be ineffective, costly and certainly not free of biosafety risks.

Researchers led by Dr Loaiza at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Panama aimed to understand the causes for the expansion of the Tiger Mosquito in the country. The species is native to South East Asian. It was first detected in Panama in 2002, but had been in other parts of the Americas since the 1980s. It had also spread to Europe in the 1970s and Africa in the 1990s.

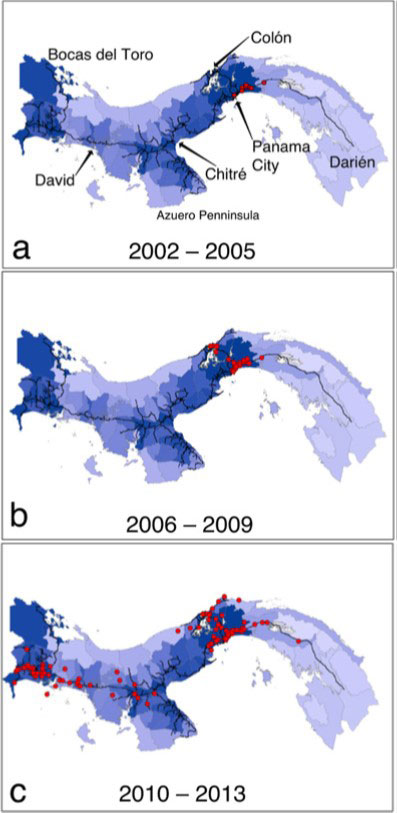

Mapping the expansion of its range, the researchers used models to see which factors promoted the spread of the Asian tiger mosquito in Panama. By looking at models of road networks, population density, climate, as well as all these factors combined, they found that road networks most accurately correlated with Asian tiger mosquito expansion, while climactic factors correlated most poorly. This may be due to the fact that the whole country has the right climate for the mosquito to survive and flourish. As shown in figure 1, since 2002, the Asian tiger mosquito has spread from the eastern neighbourhood of Panama City to the Caribbean coast and western parts of the country by 2013. Their modelling data suggests that controlling the transportation of larval and adult mosquitoes need to be priority if the spread of the species is to be controlled.

Figure 1 Expansion of Asian tiger mosquito across Panama from 2002-2013.

From 2002-2005 (a) the species was detected only in Eastern parts of the capital, Panama City. From 2006-2009 (b) it expanded out of the city and along the Caribbean coast and by 2009-2013 (c) it has invaded much of western Panama as well as east of Panama City.

Strategies focusing on the Yellow fever mosquito include the British firm Oxitec’s release of its first batch of GM Yellow Fever mosquitoes in Panama in May 2014. The GM mosquitoes were engineered to include a sterility gene in the males, which do not bite with the principle being that GM males will breed with wild-type mosquitoes in order to bring down overall population numbers. Oxitec have also released their insects in the Cayman Islands, Malaysia and Brazil, with plans for releases in Florida later this year. Florida citizens have reacted furiously to this proposal with a petition against the release drawing over 145 000 signatures on just one day [3].

Fumigation programs in Panama also preferentially target the Yellow Fever species, which inhabit densely built-up areas as opposed to in vegetation outside of buildings, where the Asian tiger mosquito is more commonly found.

As cautioned by the new study, the major problem with the current GM and fumigation control programs targeting the Yellow fever mosquito for disease control, is that the Asian tiger mosquito has been increasing in population size in many regions of the Americas. In many parts of the US it has even overtaken the Yellow Fever mosquito as the dominant species [4]. That is indeed the case in much of Florida where it is now become the most common species to bite humans, making the proposed release of GM mosquitoes in the State an uninformed and potentially dangerous approach to effective disease control. In Gabon and Cameroon, the rapid invasion of the Asian tiger mosquito is thought to be responsible for the 2007 epidemic of dengue and Chikungunya viruses, with local outbreaks of disease corresponding with high density of this species. Yellow fever mosquitoes also populate these regions but are thought to have played a secondary role in that outbreak [5].

One well-supported mechanism for the decline in the Yellow Fever mosquito is its intense competition for resources with the Asian tiger mosquito. The spread of the Asian tiger species makes control programs targeting only the Yellow Fever mosquito likely ineffective, and may even exacerbate the spread of the Asian tiger mosquito by leaving behind an empty ecological niche for them to fill. The authors further warned that the Yellow fever mosquito could re-establish itself in the absence of continued release of GM insects, which would prove the GM strategy to be a very costly, short-term solution.

Commercial releases of Oxitec’s mosquitoes in Brazil have already coincided with a dengue epidemic that pushed local authorities to declare a state of emergency [6]. Though the reason behind the epidemic remains unclear, this highlights the worrying lack of understanding that these releases have on the local ecosystems and most importantly, on human diseases which these releases are purportedly aiming to eradicate.

This is an additional concern to the lack of risk assessment carried out on the GM insects made by the British firm Oxitec. Many risks regarding these mosquitoes have been raised and warrant a complete halt to any further release until comprehensive data on their biosafety are published [7]. Even for controlling the Yellow Fever mosquito, the strategy has many flaws that make it potentially inefficient, ineffective and hazardous (see [8] Transgenic GM Mosquitoes Not a Solution, SiS 54).

Regulations for GM insect release are also lacking, with no specific regulations existing in any country. The UN Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety states that when exporting GM insect eggs to another country, the producer is supposed to supply a risk assessment that meets EU standards and to copy this to the EU and UK authorities so it can be made public, something which Oxitec has not done [9]. Furthermore, releases in the Cayman Islands and Malaysia were done without public consent (see [10] Regulation of Transgenic Insects Highly Inadequate and Unsafe, SiS 54).

Concerns about fumigating with toxic pesticides is another problem for disease containment and the least toxic strategy possible must be used in order to protect people from not just the viruses, but other health problems associated with pesticide exposure. To date, one of the most effective and also non-toxic control measures is to target their larval habitats, i.e., any objects or spaces that collect water such as empty tyres, plant pots, leaking drains, pipes and so on. There are other new and safer strategies being developed such as the use of a common symbiotic bacterium Wolbachia that prevents dengue virus multiplying in the mosquito host (see [11] Non-transgenic Mosquitoes to Combat Dengue, SiS 54).

GM strategies have thus far been based on an over-simplified and short-sighted understanding of how to manage nature, with its constant ability to adapt and modify to survive. The new study serves as additional warning that all releases of GM mosquitoes should cease.

Article first published 09/09/09

Comments are now closed for this article

There are 3 comments on this article.

Douglas Hinds Comment left 10th February 2015 07:07:09

The new study serves as additional warning that all releases of GM ORGANISMS should cease.

Todd Millions Comment left 12th February 2015 08:08:24

Last(questionable) report I have is that for US release of Oxitec Mossies-'workers are hand separating (what could possibly go wrong?) the males'. I would like this too be confirmed,but the malware levels of terminals available too me are currently running at facebook levels.As well as this-If the Asian tiger mosquito referred too is the same one that arrived from Japan too Texas via car tires in the 1980's-It is cold hardy as well and has being spotted as far north as Montana.I think they have made it across the Canadian border,but my specimens have being lost and Ag canaduh wasn't interested in them when I gathered them a decade ago.I'll look for more.

Patricia P. Tursi, Ph.D. Comment left 16th February 2015 18:06:38

This is another excuse to replace all nature with synthetic life forms, This includes plants, animals, humans and microbial life. AI is being merged with humans via Morgellons (Clifford Carnicom research). NASA scientist, Dr. Steven Dick sees a future where AI will replace biology and that is the plan through DARPA, genetic engineering and other programs. This is one step toward that goal. See the Post Biological Universe.