Amid a rising epidemic of farmers’ suicides in India, an organic farmer appeals to the father of the Green Revolution to embrace organic agriculture.

Sam Burcher

India has enough food to feed her population of one billion, yet hunger and food insecurity at household level increased at the end of the 20th century. A new UN report casts doubt on the government’s claim that poverty declined from 36 to 26 percent between 1993-2000 [1]. It criticizes the shift to cash crops that reduced the cultivation of grains, pulses and millets for household consumption. The report slams the rise of farmer suicides in India and links them to the unremitting growth of a market economy that does not benefit all Indians equally.

Bhaskar Save is an 84-year-old farmer from Gujarat who has petitioned the Indian Government to save India’s farmers from exploitation and worse. In an open letter to Prof M.S. Swaminathan (chairperson of the National Commission on Farmers in the Ministry of Agriculture) he puts the blame squarely on his shoulders as the ‘father’ of the ‘Green Revolution’ that has destroyed India’s natural abundance, farming communities, and soil [2]. He writes: “Where there is a lack of knowledge, ignorance masquerades as science! Such is the ‘science’ you have espoused, leading our farmers astray – down the pits of misery.”

The Green Revolution defines the forty years after India’s independence in 1947 when technology was widely introduced into agriculture. Farmers came under intense pressure to provide marketable surpluses of the relatively few non-perishable cereals to feed the ever-expanding cities. Since then, India’s integration into the global economy has served transnational corporate interests championed by the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO, but not her farmers [3]. Fifteen years of market reforms guided by the international financial superstates have unleashed a second wave of agrochemicals, biotechnological seed and pesticides into the Indian countryside with devastating effect.

Mumbai and Bangalore have benefited from the boom in the information technology sector that contributes an eight percent growth to India’s economy each year [4]. The two cities are now poised to take advantage of the boom in the biotech industry. The picture of “India shining” touted by an expensive government backed media campaign is considerably clouded by the rural areas being torn apart at the roots by biotechnology. The countryside is home to 70 percent of India’s population.

The second ‘Gene Revolution’ in agriculture is proving more deadly in the wake of the first. The cost of taking on the extra burden of gene biotechnology is too much to bear. Farmers unable to pay back debts incurred by the purchase of seed, pesticides, fertilizers and equipment, kill themselves at a rate of two per day. In despair some drink the chemical pesticides, while others burn, hang, or drown themselves. At a help centre set up to monitor farmer suicides in Vidarbha region in the central state of Maharashtra, black skulls mark the number of dead farmers on the map. There are 767 skulls clustered together that were pinned up in fourteen months to August 2006. India’s agricultural minister Sharad Pawar acknowledged in Parliament that a total of 100 000 farmers have committed suicide between 1993-2003 [5]. A further 16 000 farmers per year on average are said to have died since then.

“You, M.S. Swaminathan…More than any other person in our long history it is you I hold responsible for the tragic condition of our soils and our debt-burdened farmers, driven to suicide in increasing numbers every year.” Bhaskar Save writes.

Nearly all who died farmed the once profitable cotton crop known as “King Cotton” from the days of the British Raj. Now it’s called “Killer Cotton” not just because the cost of inputs has increased, but the state also cut its guaranteed purchase price by 32 percent, and buys less of the harvest than before, leaving farmers to find other buyers who tend to pay low prices. Competition from foreign trade has intensified as reduced import duties give heavily subsidized US cotton an advantage.

The final nail in the farmers coffin is expensive genetically modified (GM) cottonseed that has proved disastrous for the small, non-irrigated plots common to most of India’s hundreds of millions of farms [6] (Indian Cotton Farmers Betrayed). Farmers encouraged by agricultural officials to increase productivity try to do so by borrowing money to buy Monsanto’s expensive cottonseed. Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and US President George Bush agreed the Knowledge Initiative in Agricultural Research and Education in March 2006 that will ultimately bring Indian agriculture under the control of US corporations like Monsanto. Transgenic animals and poultry are also part of the deal. The Indian government’s ability to protect farmers, consumers and the environmental health from the risks of GM crops has been called into question [7] (Outsourcing Ecological and Health Risks & Reducing Scientists to Bio-coolies for Industry).

The recent Supreme Court of India’s decision to ban any further GM crop trials until further notice [8] will force the government to rethink its biotechnology strategy. Unfortunately, existing GM cotton trials are not included in the ban despite documented health hazards to humans and livestock [9, 10] (More Illnesses Linked to Bt Crops; Mass Deaths in Sheep Grazing on Bt Cotton).

Prime Minister Singh has now invested a hefty Rs 160 billion in a debt relief package to persuade farmers in the high-risk suicide areas of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharastra to continue farming [11]. The package consists of loans, interest waivers, seed replacement, minor irrigation schemes, and subsidiary incomes for farming livestock, dairying and fisheries. The investment comes too late for those farmers that have already died. Many more have already turned their backs on the perils of Bt cotton farming to regain their health and independence [12] (Message from Andhra Pradesh: Return to organic cotton & avoid the Bt cotton trap).

Perhaps it is not surprising that farmers fall for the promise of increased productivity by buying the long list of equipment from the agribusiness salesman. According to Bhaskar Save, of the 150 agricultural universities in India that own thousands of acres of land, not one grows any significant amount of food to feed its staff and pupils. Instead the focus is on churning out hundreds of graduates each year to tell farmers what they must buy to increase productivity, not what they must do to ensure the sustainability of the land for future generations.

“Nature, unspoiled by man, is already most generous in her yield. When a grain of rice can reproduce a thousand-fold within months, where arises the need to increase its productivity?” Save asks Swaminathan.

Save’s own orchard-farm “Kalpavruksha”, near the coastal village of Dehri close to the Gujarat-Mararashtra boarder, has become a “sacred university” specialising in natural abundance, or Annapurna [13]. Every Saturday afternoon the farm gates open to farmers, agricultural scientists, students, senior government officials, and city dwellers, who come to share Save’s philosophy and practice of natural farming: “Co-operation is the fundamental Law of Nature.”

The high yields in the organic orchard easily out-perform any farm using chemicals and this is apparent to its many visitors. Masanobu Fukuoka, the renowned Japanese natural farmer said: “I have seen many farms all over the world. This is the best. It is even better than my own farm.” The coconut trees produce an average of 400 coconuts per tree annually; some produce more than 450 coconuts, and are among India’s highest yielding trees. There is an incredible variety of fruit trees: banana, papaya, mango, lime, tamarind, pomegranate, guava, custard apple, jackfruit, date, and chikoo (similar to lychee) which produces an average of 300-350 kg of delicious fruit per tree each year.

Fruit trees are also planted on soil platforms raised by Save above the rice crop in low-lying paddy fields. Between every two adjacent platforms are trenches that act as irrigation channels in the dry season and drainage in monsoon. As the trees grow, the trenches are placed further away from the trunks to encourage the roots to spread out to optimise water efficiency. This pioneering feature of his work has greatly increased yield, and attracted attention all over the world.

Diversity of plant life is the key factor on organic farms. Save simultaneously plants short life-span (alpa jeevi), medium life-span (madhya-jeevi), and long life-span (deergha-jeevi) species. The community of dense vegetation ensures that the soil’s microclimate is well moderated all year round. The groundcover provides shade on hot days, while leaf litter (mulch) cools and slightly dampens the surface of the soil. On cold nights it serves as a blanket that conserves heat gained during the day. High humidity under the canopy of mature long-life trees reduces evaporation, and minimizes the need for irrigation. The drooping leaves of plants act as a water metre to indicate falling moisture levels.

Save grows a tall, native variety of rice, Nawabi Kolam, that is rain-fed, high yielding, and needs no weeding. After harvest, he seasonally rotates several kinds of pulses, winter wheat and some vegetables on the paddy field that grow entirely on the sub-soil moisture still present from the monsoon. When they too are harvested, cattle can browse the crop residue and provide dung fertilizer to further enrich the soil for the next cycle of planting.

The polyculture model produces a year round continuity of harvests. First from the short life-span species such as the various vegetables, and then from the medium life span species such as banana, custard apple and papaya, until the long life-span species of coconut, mango and chickoo begin to bear fruit. It provides self-sufficiency for a family of ten (including grandchildren) and an average of two guests from a modest two-acre plot. Most years, a surplus of rice is gifted to relatives or friends.

Bhaskar Save was not always an organic farmer. At first, he used chemical fertilisers together with dung manure for his vegetable plants and rice paddy. His rice harvest was so good that it attracted the attention of the Gujarat Fertilizer Corporation. They asked him to teach other farmers to use the chemical fertilizers for which he received 5 rupees for every bag he sold. He quickly became a “model farmer” for the new technology while earning enough to extend the acreage of his farm. Soon he realised that he was caught in a cycle of spending more money to use more chemicals to maintain productivity. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi and his successor Vinoba Bhave, he adopted some of the farming methods of the Adivasi, the tribal majority of India’s rural population. From then on his costs reduced and the soil flourished. By 1959-60 he abandoned chemicals altogether.

Save has learned his major lesson: “By ruining the natural fertility of the soil, we actually create artificial ‘needs’ for more and more external inputs and unnecessary inputs for ourselves, while the results are inferior and more expensive in every way. The living soil is an organic unity, and it is this entire web of life that must be protected and nurtured”

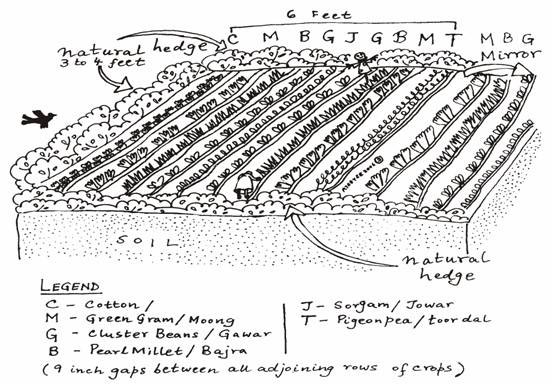

Save has updated a traditional intercrop system specifically for growing cotton in low rainfall areas (see fig 1). The six integrated crops are harvested in stages during a 365-day cycle: two types of millet, three kinds of edible pulse legumes, and cotton. Every other row of legume crops provides nitrogen to the soil. Weeds that attract predators that feed on crop damaging species are welcome. So are worms that aerate and provide compost, and nutrient rich soil microrganisms. All are the natural keepers of soil health. As this system needs no irrigation, it is crucial that chemicals are not added as they diminish the soils capacity to absorb moisture.

fig 1

For millennia organic farming was practiced in India without any marked decline in soil fertility. In areas where polyculture is replaced by monocrops such as sugarcane and basmati rice the soil is ruined by the excessive use of water irrigation.

Thick crusts of salt (salinisation) progressively form on the waterlogged land where roots rot. Supplying huge amounts of water for refined sugar that requires 2 to 3 tonnes of water per kilo has encouraged extensive dams and river linking schemes by industry. These short-term solutions displace people and wreak devastating ecological consequences.

In contrast, organic farming practice is light on irrigation. The best yields come from soil that is just damp. Porous soil under Save’s organic orchard of mixed local crops acts like a sponge, soaking up the huge quantities of monsoon rains that percolates down to the ground water table. Restoring a minimum of 30 percent of mixed indigenous trees and forests to India within the next 20 years could prevent the impending threat of water scarcity. Storing water underground in natural reservoirs is the way forward to ensure food and water security.

As Save points out, “More than 80% of India’s water consumption is for irrigation, with the largest share hogged by chemically cultivated cash crops. Most of India’s people practising only rain-fed farming continue to use the same amount of ground water per person as they did generations ago.”

Bhaskar Save’s method of mixed short to long life span intercrops on plots as small as two acres proves that it is possible to regenerate even barren wastelands in less than ten years. This is the revolution that India’s small farmers need as transnational corporations threaten to impose a new kind of serfdom with patented biotech crops. Save’s sixty years experience shatters the illusion that farmers can boost productivity and profits by increasing inputs of agrochemicals and engineered seeds. S.M. Swaminathan must embrace organic farming models that can revive the fortunes of Indian farmers and negate the need for costly debt relief packages when coordinating the new Agricultural Policy.

Article first published 12/10/06

Got something to say about this page? Comment